Caesar affirms his staunch atheism in his letters to Turrinus, and explores the role of religion in Rome. In the third book, Wilder examines religion. Matters come to a head at a party thrown by Cleopatra, where Caesar and his retinue discover Mark Antony and Cleopatra in flagrante delicto.

Caesar analyzes and criticizes Clodia’s behavior. Clodia turns suddenly bitter towards Catullus, and some of his more despairing poetry is included, translated into English by Wilder, using the original, complex Latin meter. Caesar remarks at length on her character in letters to Turrinus, and Pompeia consults Clodia about the best way to receive her rival. The second book, Wilder declares, “contains material relevant to Caesar’s inquiry concerning the nature of love.” The book primarily treats the visit to Rome of Cleopatra, whose prior love affair with Caesar has produced a son. After being treated by his doctor, he returns to the dinner and, despite his wounds, arranges a Greek-style symposium with a discussion of whether poetry is the work of men’s minds or divine inspiration. To Pompeia’s distress, Caesar declines, but is later forced to reconsider on the way to dinner, he narrowly escapes an assassination attempt. Clodia invites Caesar, Catullus, the orator Cicero, and various other dignitaries to a dinner. Wilder also introduces Clodia Metelli, her tumultuous love affair with the poet Catullus, and the resulting scandals and Caesar’s relatively simple-minded wife, Pompeia. Throughout the novel, Turrinus operates as Caesar’s philosophical sounding board and gives the reader relatively direct access to his thoughts. Most well represented is Wilder’s Caesar, especially through his journal-letters to the fictional Lucius Mamilius Turrinus, a boyhood friend of Caesar’s who lives in solitude on Capri after being captured and maimed during one of Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul. The first book introduces the reader to Wilder’s main characters, both as authors and through the correspondence of others.

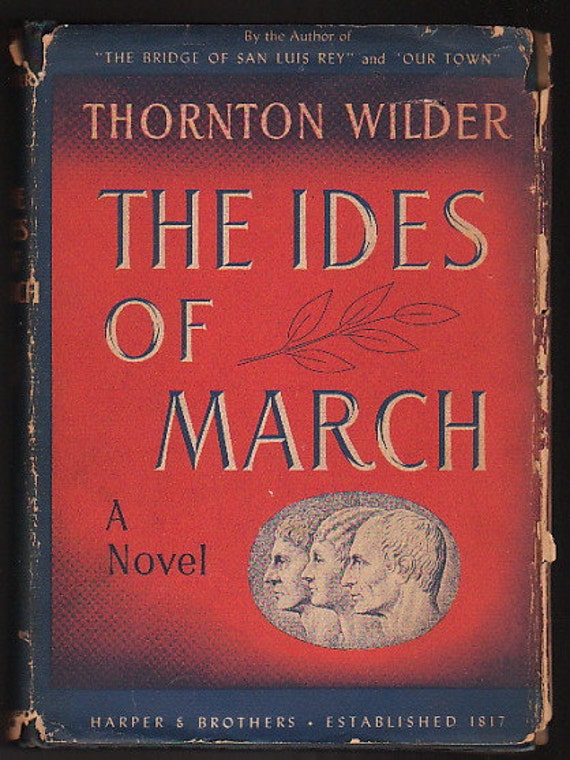

The first treats September of 45 BCE the second begins in August and ends in October, and so forth. The documents are arranged into four books, each beginning earlier and ending later than the one that precedes it. Wilder’s introduction to The Ides of March terms it “a fantasia upon certain events and persons of the last days of the Roman republic.” Unlike any of his other works, the novel is constructed as a series of imaginary documents, though a few genuine passages-usually poems of Catullus-are interspersed at applicable points. Thornton Wilder called it “a fantasia on certain events and persons of the last days of the Roman republic.” Through vividly imagined letters and documents, Wilder brings to life a dramatic period of world history and one of history’s most magnetic, elusive personalities. The Ides of March is a epistolary novel set in Julius Caesar’s Rome.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)